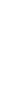

By becoming a member of FoundMyFitness premium, you'll receive the Science Digest every-other-week covering the latest in my exploration of recent science and the emerging story of better living — through deeper understandings of biology.

- Ketogenic diet, by replacing glucose with ketones as an energy source, lessens alcohol cravings among people with alcohol use disorders.

- Omega-3 fatty acids reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease-related death by up to 23 percent, especially in people with high triglyceride levels.

- Women see a 24 percent drop in premature death risk with just 140 minutes of weekly activity – half the time men need for similar benefits.

- Aging undermines the brain's capacity for maintaining working memory, with subtle declines in neuron activity and connectivity in the prefrontal cortex.

Laboratory and animal studies suggest lithium could protect the brain from cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease, but results from human trials have been mixed. To clarify the picture, researchers combined data from multiple clinical trials to test whether pharmaceutical lithium salts have meaningful benefits for brain health.

The authors systematically reviewed and meta-analyzed six randomized, placebo-controlled trials (435 participants) that compared lithium supplementation with placebo in studies lasting roughly 10 weeks to 24 months. All participants had either mild cognitive impairment, a stage of measurable decline that can precede dementia, or Alzheimer's disease. The main outcome was change in cognition, and the tested lithium salts were: lithium carbonate, lithium sulfate, and lithium gluconate.

- When results from all six trials were combined, lithium was similar to placebo for cognitive outcomes.

- In the primary analysis, which prioritized the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog), the average difference between lithium and placebo was small and could not be confidently attributed to the treatment rather than chance.

- Follow-up analyses that relied on different cognitive measures or prioritized different tests reached the same conclusion and showed no consistent cognitive benefit from lithium.

- Measures of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, such as agitation and related behavioral problems, were similar between lithium and placebo groups.

- Subgroup analyses found no differences based on diagnosis (mild cognitive impairment vs. Alzheimer's disease), study duration, lithium dose, or lithium salt type.

- One study suggested a stronger effect from lithium, but it was judged to be at high risk of bias, making its result unreliable.

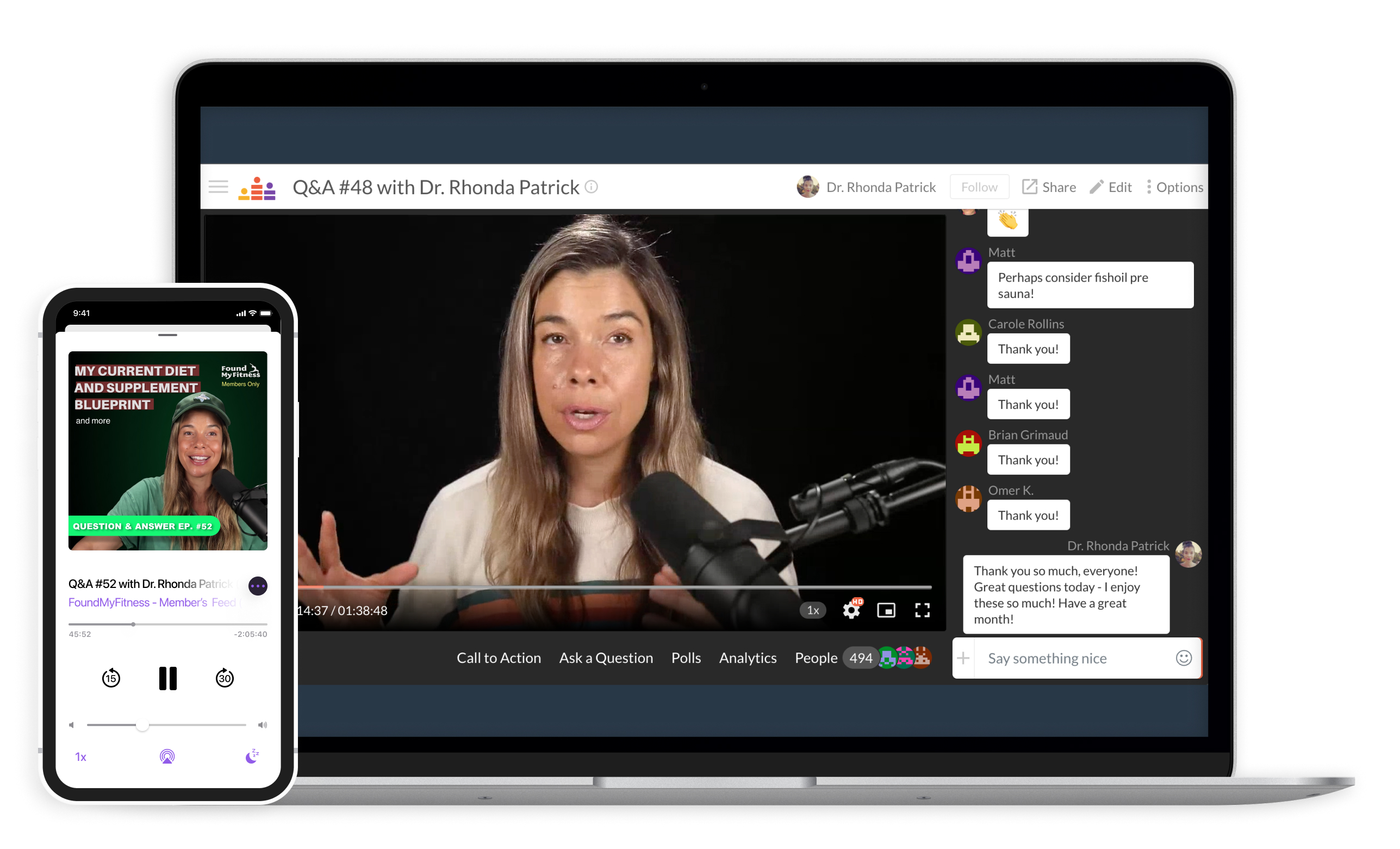

Lithium's biological effects may depend strongly on its chemical form and how it behaves in the brain. Studies in animals show that lithium can stick to amyloid-β, the protein that forms plaques in Alzheimer's disease. When this happens, lithium becomes trapped inside plaques instead of remaining available to brain cells, where it could help regulate inflammation, communication between neurons, and limit harmful changes to tau, a structural protein that helps stabilize neurons. Commonly tested lithium forms, especially lithium carbonate, appear more likely to bind to amyloid plaques in this way. By contrast, laboratory and animal studies suggest that lithium orotate, a different chemical form, may enter brain cells more easily and avoid plaque binding.

Importantly, the clinical trials analyzed here did not test lithium orotate, only carbonate, sulfate, and gluconate. As a result, the study supports the conclusion that standard lithium supplements do not slow cognitive decline in people with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer's disease, while leaving open the possibility that other lithium formulations could be more effective. In Q&A #69, I discuss the benefits and risks of low-dose lithium supplementation.

Dementia that develops before age 65, often called early-onset dementia, is relatively rare but can profoundly disrupt cognitive function, independence, and daily life for both individuals and their families. Many cases appear to be influenced by lifestyle factors, yet diet has received little attention in this younger age group. To address this gap, researchers examined whether blood levels of omega-3 fatty acids in midlife are associated with the later development of early-onset dementia.

Using data from the UK Biobank, the team studied more than 217,000 adults between ages 40 and 64 who did not have dementia at the start of the study and were followed for an average of about eight years to track new dementia diagnoses recorded in hospital and death records. Instead of relying on food questionnaires, they analyzed omega-3 levels measured in participants' blood. The researchers focused on three measures: total omega-3 fatty acids, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, the most abundant omega-3 in the brain), and non-DHA omega-3s, which include other omega-3 fatty acids found in fish and plant foods.

- During follow-up, 325 participants developed early-onset dementia, representing about 0.15% of the study population.

- Participants in the fourth and fifth quintiles of blood omega-3 had about a 38% and 36%, respectively, lower risk of early-onset dementia compared with those in the lowest quintile.

- DHA on its own showed a less consistent and robust association. Although the highest DHA quintile had about a 35% lower risk than the lowest, no clear reductions were seen across the middle quintiles.

- Non-DHA omega-3 fatty acids showed the strongest association. Participants with moderate to high levels of non-DHA fatty acids had a 37-42% reduction in risk compared with those with the lowest levels.

- The link between omega-3 levels and dementia risk did not differ meaningfully based on APOE ε4 status, so the pattern looked broadly similar in carriers and non-carriers.

Omega-3 fatty acids are biologically linked to dementia risk because they are used to make signaling molecules that actively regulate inflammation, including inflammation within the brain. Chronic brain inflammation is increasingly recognized as a contributor to neurodegeneration. Experimental studies also show that omega-3s influence processes such as the generation of new neurons and the stability and function of neuronal membranes. In this study, stronger associations for total and non-DHA omega-3, compared with DHA alone, suggest that omega-3 fatty acids beyond DHA may meaningfully contribute to these mechanisms, consistent with evidence that different omega-3 types act through overlapping but not identical biological pathways.

Taken together, the study further strengthens the biological and epidemiological case for omega-3 fatty acids as a plausible, low-risk target for future prevention research, particularly in midlife. In this clip, Dr. Axel Montagne discusses how the brain transport of omega-3 DHA may be important for the prevention and possibly as a therapy for dementia.

Caffeine is a widely consumed psychoactive substance, but its long-term metabolic effects are often hard to isolate because coffee, tea, and soft drink habits correlate with many other health-related behaviors. To address that problem, researchers used human genetics to ask whether long-term differences in blood caffeine levels relate to adiposity and cardiometabolic disease.

The researchers applied a method called Mendelian randomization, which uses naturally occurring genetic differences to explore cause-and-effect relationships. Because inherited genetic variants are fixed at conception, they create natural groups that are largely not shaped by later habits or environmental factors. In this study, the researchers focused on two genetic variants near the CYP1A2 and AHR genes, which are involved in regulating how caffeine is metabolized in the body. The team then linked these caffeine-related differences to large genetic datasets containing information on body mass index (BMI, a weight-to-height measure), body fat, type 2 diabetes, and major cardiovascular diseases.

- People with genetic variants linked to higher predicted blood caffeine tended to have lower BMI.

- Higher genetically inferred blood caffeine levels were associated with lower whole-body fat mass, while lean mass, which includes muscle and organs, showed no meaningful change.

- Individuals with genetically predicted higher caffeine levels had a lower risk of type 2 diabetes.

- When the researchers examined possible pathways, they estimated that about 43% of the lower diabetes risk could be attributed to reductions in BMI.

- No strong links were found between higher predicted blood caffeine levels and major cardiovascular diseases, including ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, or stroke.

- The same genetic variants linked to higher caffeine levels were also associated with drinking less coffee and tea, likely because people who metabolize caffeine more slowly tend to consume less of it to achieve the same stimulant effects.

Slower caffeine breakdown keeps circulating levels elevated for longer periods, which may increase energy expenditure through caffeine-induced thermogenesis and fat oxidation. Experimental work suggests caffeine enhances mitochondrial activity, increases sympathetic nervous system signaling, and shifts brown fat tissue toward a more metabolically active state. Caffeine has also been shown to increase satiety and reduce energy intake in some settings. Over years, even small increases in daily energy expenditure and decreases in energy intake could meaningfully alter fat accumulation and downstream insulin signaling.

Because this genetic analysis reflects lifelong caffeine exposure rather than a specific intake level, it cannot indicate an effective dose, and its reliance on only two variants from mostly European datasets further limits precision. Even with these constraints, the study provides causal evidence linking sustained caffeine exposure to metabolic benefits. In episode #103, I synthesize extensive research to illuminate how the timing, brewing methods, and additives to coffee influence its health benefits and risks.